“David!” exclaims the three-year-old, each time he sees me.

For about a year now, this boy would exclaim loudly my name each time we crossed paths.

It didn’t start that way. At first, having just turned three, he was quite shy. Holding onto his mother, he would peek at me, a new stranger entering his life.

At some point, apparently, in that developing little mind, came what was probably acceptance. This larger human, not in my family, is someone who I see with some regular occurrence. With each meeting, the surprisal is reduced and familiarity increased. “Look, it’s David, he lives upstairs!” Mother would say. Thus “David from Upstairs” has been conceptualized.

Or rather, conceptualizing. With each “David!” he exclaims, he’s solidifying the verbal signifier “David” being connected to the human in front of him, quite literally “real-izing” my object permanence – as he has done with mom, dad, and eventually many many more people, objects, concepts, etc.

Likewise, my mother tells me that when I was young, one of my favorite activities was sitting by the road in front of our apartment complex and pointing out the different types of cars. Especially trucks apparently, maybe because the Chinese term for truck,卡车, was somehow easier or something, I don’t know. Regardless, with each semi-conscious announcement of “Name of Object” in association with “Object”, my mind wires map and territory together.

The kind of learning happening here is relatively well-studied (though not necessarily well-understood yet). From cognitive science and child developmental theory to machine learning, we have described different frameworks of how learning loops with feedback enable the integration of ideas or concepts into the “mind” of a given “entity” be that a child, a pet, or an AI model.

Curiously though, “child”, “pet”, and “AI model” are all “other” entities that we are paying attention to – and think deserve attention. Specifically “other” entities that are ostensibly younger, weaker, and less capable. Somehow, we didn’t quite develop the same kind of awareness for our own learning loops.

Allow me to illustrate with a little story.

Many years ago, I went to my first math camp and had an extraordinarily enjoyable experience. Graced by some friendly and talented STEM students and teachers, I was immersed for two weeks in an environment that talked about math (but really any subject) in a way I couldn’t have imagined when I was in school. To be clear, I never quite liked math and was broadly just hoping to be “done with it” after school. Yet math expressed here was fun. It was more than fun even, it was beautiful.

For a while, after the camp was over, maybe a month or two, I described everything as a “function of variables”.

Thinking about finding a new job? “That’s a function of optimizing between desired variables like salary and available offers.”

Need to write a paper? “That’s a function of your motivation and time available.”

Feeling sad? Not sure how to talk to a friend? “Consider a function that describes the problem!”

My girlfriend at the time hated this. For good reason too! It was impossible to communicate with me unless it was through some abstract math-like analysis.

Whether it was appropriate or not, I had to at least slap the function idea on it just to see if it fit. After all, the motions of celestial bodies can be described by functions, so why not this?

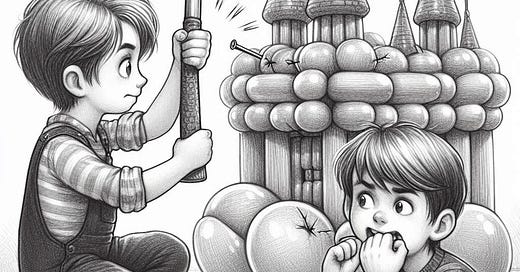

We sometimes call this: “When you are holding a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

Somehow though, it’s easier (and cuter) to have a three-year-old yell out “Car!” every time they see a car, than a grown man ceaselessly going “FuNCtiOnS!!” over dinner.

I think two factors help create this phenomenon.1

The first is conceptual. We easily categorize “child” as developing and their learning as still “in process”. Our notion of an adult, however, doesn’t nearly get the same leeway. In fact, for many, almost as soon as we’ve graduated from the category of “this pure, innocent, child” to “my 6 years old” or “my middle-schooler” to “my manager” to “my president”, there emerges a pressure of “one should already know”. It means that we expect someone to already know “how to cook”, “how to do taxes”, or “how to speak clearly”. If they don’t already know these things, then they should be able to learn them stoically, effectively, and with no more than “LinkedIn-appropriate” fanfare.

The second is logistical. Most of us have our attention quite occupied in our daily lives. With limited attention, it’s better to put my patience with the learning child (who needs the attention), rather than the adult (who should know better after all). This also means that when parents or teachers end up being overstrained, they may also either angrily say “Enough with the Cars already!” or a disassociated tired “Yes, yes, another car.” – despite potentially being quite aware of the fact that, like her first steps, it’s the joy in the parents’ response, that makes her drawn to getting up again after the inevitable fall. If this is with our partners though, the person we got into a relationship with because we thought they were so lovely, incredible, wonderful, well … “I don’t have time to teach you how to fold your clothes properly at 25.” Oh, and god forbid if it’s our parents who are the ones learning instead.

Irritating as my “Functions” stage certainly was, it’s helpful to keep in mind that, like the infant learning that cubes go through the square hole without needing to test it after some time, eventually we do "learn".

It's tricky to assume learning here to mean "complete" though. I'll define "Learned" as: sufficiently paid-attention-to that it falls away from salience, into the background, latently available to be connected with all the other things we have "learned". After all, our lives keep unfolding and many things are competing to become the new thing we are learning instead.2

This also helps explain why sometimes when we think we've learned something, it can come back into salience again after some time (haunting us even). Say, I thought I finally learned to be confident (i.e. I had a period where it's actively in my attention) and thus think about other aspects of my life. However, some new circumstances revealed new aspects in which I was not confidence (as I thought I was), thus, a new loop of learning may begin.

In both my experience and observations, cases where people are encouraged in their cycles of learning tend to find the process more enjoyable while achieving higher degrees of mastery.

Big revelation, I know.

The question is all in the execution, because on the other end of “probably everyone agrees” is “oh they are just going through a phase” to “here they go again on this.” It’s not just a simple matter of having patience for each other, but rather learning to pick up our co-responsibilities in informing and facilitating each other’s dynamic, simultaneous learning processes. This can be especially difficult when we believe the things each other is learning is not “useful”.

For example, I have typically not found makeup to be particularly “useful”. As someone focused on being “productive with important things”, why should anyone spend 30 minutes to an hour every day doing up their face only to take it off at the end of the day. At least in part due to the disposition, this is a subject that would never come up in conversation, partially because it wouldn’t be relevant (as dictated by me). It’s an expensive and time-consuming hobby that mostly compresses down to “Are you ready yet? It’s been 20 minutes already, we are going to be late.”

As a result, when my partner’s birthday was coming up, and she brought up the idea of wanting some new makeup brushes for a gift, my initial reaction was “Ehh, surely there are better gifts.” This reaction of mine, which happens often enough, is subsequently met with conflicted feelings – I know she genuinely likes makeup and values it.

From here, lies a fork in the road. I could essentially agree to disagree, accepting that she finds value in it while also accepting I do not find value in it, thus simply letting it be. Alternatively, I could wonder about why it was that she finds value in something that I so deeply don’t find value in – an interesting phenomenon surely – and seek to understand more about myself and the person I share life with.

In an innocent question of why a certain makeup brush was twice the cost of another (they looked the same to me after all), it occurred to us that we could do a little workshop where she introduces Makeup and Beauty to me and that this would be a good idea. The workshop ostensibly is to teach me about how makeup works, but it also achieves several additional things that are valuable to both of us and our relationship – remember, a learning context that encourages multi-lateral learning is what we want to cultivate:

Starting off, she has the space to talk about something she loves.

Not only that, she gets to learn more deeply about a subject she values through preparing and teaching me.

We then get to learn more about how she shares and teaches, in a way that paves the path for future such instances – even more sharing of one’s joy and aliveness.

We also gain the prior that we are willing to learn and gain from each other’s interests, even if it may not appear obviously relevant.3

Unsurprisingly, in a workshop taught by someone genuinely passionate about the subject coupled with someone open and curious about the subject, interest and usefulness in the subject was gained.

Most profoundly, I found that makeup was a lens through which I could re-understand faces in general. In a moment when we were talking about how eyebrows are gelled and drawn in, I looked in the mirror and noticed my eyebrows popping out with a level of detail that was almost psychedelic. When coupled with a lot of conceptions around beauty as definitive of one’s worth, I understand this creates the hyper-critical mindset that is unable to unsee the “imperfections” natural to any human face, especially one’s own. Without these conceptions though, it grants a degree of detail and thus new layers of appreciation for features of different, unique faces. How one person’s cheekbones hold up their face, and how if some bronzers are added, it could enhance those features to artistic heights. I’m quite excited to make a Sephora field trip soon to explore what more could be learned.

Not all cases go as well as this workshop though. I try, with mixed success, to strive for the quality in this particular case study, in as many relationships as possible.

However, this can often be most difficult to strive for in the case of our loved ones. The sense of “they should already have it together” is stronger, the more intimacy there is apparently. After all, we actually care about their wellbeing. Their “together-ness” matters and can be even threatening when insufficient.

In cultivating this willingness to participate in the learnings of people – whether it's everyday people or the people close to us, we can find remarkable growth. Each case of this being successful makes the next case more possible, not just in the relationship where it's happening, but also in how both sides’ minds update the expectation that these can be possible in all relationships.

Recalling the child again, in the exclamation of “Car!”

I believe there is a simple human desire: to share and connect with other minds the marvel of what we are discovering – what we are learning.

I don’t think this changes because we are an adult. In our busy-ness and expectations, we often miss the marvels of what those around us are learning. If we can tap into that, we may find not just faster and more diverse learning cycles, but also connection and intimacy.

When One Is Holding A Hammer ... Part 2

When I first learned about attachment theory, it was because I had a nail in need of a hammer. I was fresh out of a relationship, and I was confused as to why it didn’t work out. A nagging suspicion was forming that all of my relationships were sharing some disturbingly similar pattern.

When One Is Holding A Hammer ... Part 3

As I contemplated why it was that people around me didn't like it when I was proselytizing the wonders of "Functions", here's a conclusion I came to:

One might say a function with two variables 😬.

Notably, a tangent here would be trauma. In my understanding, trauma, cognitively speaking, is a good example of learning that wouldn't fall away due to a stuck-ness on updating. The learning associated with the trauma spikes in salience and dominates any subject that triggers it almost regardless of evidence.

Illustratively, or perhaps comically stereotypically, the night before we ran this workshop, I ended up giving a two-hour introduction to Warhammer 40K. Having this back-to-back is endearing and amusing. Now I can reference spacemarines freely as a reference for contemplations on stoicism and warrior-hood 🤓.

This post reminds me a lot of my favorite quote from Robert Kegan's "Evolving Self":

Being in another person's presence while she so honestly labors in an astonishingly intimate activity- the activity of making sense- is somehow very touching. This is an experience we seem to have more often with very young people than with adolescents and adults. Is this because older people less frequently display themselves in these touching and elemental ways, or because we are less able to see those ways for what they are? The personal activity of meaning actually has as much to do with an adult's struggle to recognize herself in the midst of conflicting and changing feelings as it has to do with a young girl's struggle to recognize a word; it has as much to do with a teenager's delicate balance between his loyalty to his own satisfaction and his emerging loyalty to the preservation of reciprocal relationships as it has to do with a one-year-old's effort to balance himself on two legs; it has as much to do with an adult's immobilizing depression, or a teenager's refusal to eat, as it does with a six-year-old's inability to leave the home and go off to school. The activity of meaning has as much to do with a man's difficulty acknowledging his need for closeness and inclusion, or a woman's acknowledging her need for distinctness and personal power, as it has to do with ten year-old's need for privacy and self-determination, or a three-year-old's need to have her adhesive relationship to significant others welcomed and supported. If this book is apparently about a way of seeing others, its secret devotion is to the dangerous recruitability such seeing brings on. So perhaps the book should carry a warning. Though it is aimed at our vision, at helping us to see better what it is that people are doing, what the eye sees better the heart feels more deeply. We not only in-crease the likelihood of our being moved; we also run the risks that be-ing moved entails. For we are moved somewhere, and that somewhere is further into life, closer to those we live with.

I love this. I should maybe get my boyfriend interested in a makeup workshop