In the Civilization games, there are generally two strategies for succeeding, one could seek to “build tall” or “build wide”. To “go wide” is to build a sprawling empire that takes up as much territory as possible by building many settlements, thus gaining a large aggregate production. “Going tall” foregoes expansion in the lateral sense and instead focuses on investing deeply in a small number of cities. The tall strategy aims to optimize each city for complementarity and density/population, creating a high-production state viable against larger empires.

The strategies of “Tall” vs “Wide” is quite pervasive.

In biology, for example, species like salmon might take a wide approach to reproduction, laying thousands of eggs, knowing only a fraction will survive. Different species, like the elephant, would only birth a few offspring over the course of its life, coupled with long gestation periods.

Similarly in human society, parents might focus on having many children, expecting some of them to die in childhood, some to be married off, some might seek higher education, and some to carry “the family” into the next generation. In developed countries, the practice generally involves having few children, focusing on maximizing success for each child through piano classes, SAT prep, sports teams, and all the supplementary education common to modernity. One could say that the childrearing "meta" in the modern world favors “tall”.

It is important to note that both strategies are evolutionarily valid. It is not my intent nor disposition that the “Tall” strategy is superior to the “Wide” strategy. Instead, the differentiation here of “Tallness” has been catching my attention in a particular way. There’s something profound, yet easily neglected, in the understanding of “Tallness” that I hope to illustrate. Specifically, while both are about “growing” or “scaling”, each style has diverging philosophies. This gives it an interesting contrast to examine various dimensions of life, particularly psycho-social life, which is my intent for the next few posts.

This post is the first part of examining what “Building Tall” means. I hope to give an illustrative and intuitive sense of what “Tallness” means and feels like through our notion of Cities.1

Cities – a basis for life

The very idea of a “City” is a “tall” idea.

Instead of many small villages with huts, spread over a wide area, one of the distinguishing features of “civilization” is the concentration of people and resources. The literal tallness of the buildings that constitute a city is simply a by-product of the concentration or density that reflects the conceptual “tallness” of the city.

This density permits what economists like to harp about – specialization. It contributes to the remarkable super-linear quality that cities can demonstrate.

It can be incredibly off-putting to imagine a city filled with only sameness. Everyone living in the same buildings, doing the same job, wearing the same clothes.

A hallmark of what makes a City is diversity. No matter how homogenous a city is, we’d still imagine it to have a hospital, a school, a church, etc.

In an organic sense, cities usually evolved from smaller, less dense human settlements. The existing complexity in what might have been a township usually evolves to become more complex versions of itself. The large-ish building where village folks gathered for town halls evolved into the governance building and the local water station evolved into the fire station. Naturally, as cities grow, the new train station will replace the old one, often with the old one being repurposed for something else, becoming a cultural artifact – say a farmers market built out of the old train station. This evolutionary process gives a city its history and character – it has been composed to form Life. One can discern – yes, many things have transpired here, many people have passed through here.

Cities can also be evaluated on how “Tall” they are, as a measure of their Life and complexity.

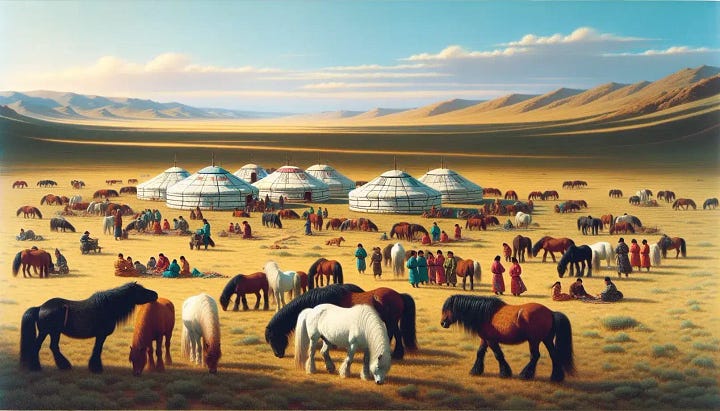

Consider these two pictures:

I’d wager that you would agree that B, the latter, is more “tall” in the sense that I am talking about here, despite the fact that the former is literally taller and more dense.

Why is this?

To be “tall” is to be imbued with complexity, with life. Tallness isn’t only density, but rather a density of coherent differences, a density of plurality, a plurality that endures.

Consider these two photos:

How far apart do you think these two locations are from each other?

About a 15-minute walk.

When I walked through both of these scenes myself, what stunned me was how wild it was that these could exist so close to each other. By some grace of the city planners, there was a striking tranquility in the temple. The city is no longer visible once I was within the park area and I had to strain to hear the noises of the city. Incredibly, this was even so for small parks of seeming insignificance, a marvel of urban design.2

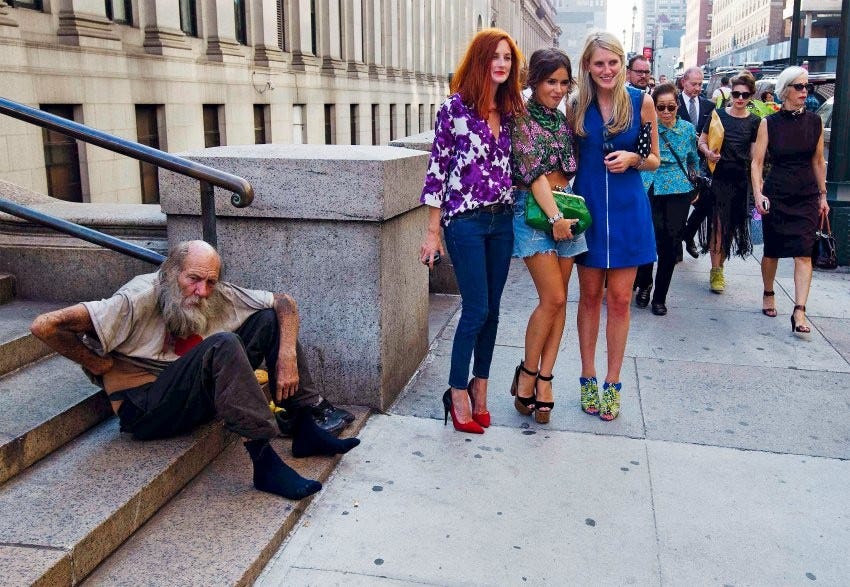

In contrast, here’s another photo that illustrates stark differences existing next to each other:

Even though both examples share the property of having two seemingly incompatible things next to each other, this one feels distinctly “wrong”.

Unlike the park and the bustling city, which has a quality of deep complementarity, the photo of the homeless screams dysergy. The former made each other more beautiful, while the latter made each other more profane. By extension, living in the environment of the former may be a balm on the soul while living in the latter would foster pathologies of ignorance.

Trickily, this incompatibility is not so simple that we could solve it simply through economic improvements. That is, even if I lift all of the homeless out of poverty and into good housing and hire people to clean up the streets, what results isn’t necessarily more “Life”; it’s more likely to look sterile.

Consider for example these photos:

And compare it to these photos:

One could say that the former, despite appearing “poorer”, still felt like it contained more life. The latter, to the extent it signals prosperity, almost appears to be a signal made by and for someone not of the city and its soul. Neither has any humans in the picture, yet we can distinctly feel more humanness existing in the former.

The life contained in the “tallness” exists in the nooks and crannies. Just like how our brain, through its folds, increases its surface area and complexity, the city that takes on layers and layers of detail gains its character. We could sense that there are stories embedded in the details; someone’s story has been through here.

With all this set, we can now assess a city (or town, etc) in terms of its “tallness”, or what Christopher Alexander would call Degrees of Life, via two means:

1. How much life is etched into the physical space

Physical space can be a reflection of the amount of life that has “left its mark” intentionally or not.

Which in the aggregate, assuming the plurality is complementary, can form cities like this:

Or fail, where plurality becomes conflicting and expresses itself like this:

2. How much life is embedded into a psychic space

Psychic space here means the dimension where we assess how much meaning has been embedded into some “space”. We can ask questions like “how much exist in the distance between the gaze of lovers?” or “how much does one star on a wall mean?”

When done well, the city reflects deep life and humanness:

However, sterility can instead be the result, where even if density exists, meaning and connection does not:

Broadly speaking then, the denser we are able to pack life coherently, the taller it is. To pack life into a space though, we usually need to let life flow through it. The London Covid Memorial would lose its density if we start vandalizing it with fake hearts and fake stories, even though we’d be adding more hearts. A building needs people living through it to gain its character.

Inconveniently, this all takes time. Especially with scaling pressures, say an influx of resources – people, gold, oil, etc. From the perspective of governors, it’s easier to manage a city through the zoning of a residential area, an industrial area, and a commercial area. The clarity allows easier management; label a thing according to its category and put the cube in the square hole. By separating them, the residential people wouldn’t be complaining about a factory in their lives, and we know to put a school in the residential area and not the industrial area. We take advantage of specialization while addressing the needs of each group. This is important! I can’t even run a company without needing to form departments after some tens of people, never mind a city with millions!

Unfortunately, this also then creates silo’ing. If I dump industrial waste with enough degrees removed from a residential zone, the residents would have little reason to care about what harm I might be creating. In contrast, if my factory was within or near the residential zone, I bet my neighbors would have some pretty strong opinions if I started bellowing toxic fumes right over their heads. The segmentation disrupts the interconnectivity of the city’s ecology. It would be like saying: ok the frogs can all live in this pond, and then the fish can live in that meadow over there – about as fragile as the marine section of an Asian supermarket.

When silo’ed, we lose the ability to mingle and discourse, and thus lose out on the very benefit of the city itself – cross-pollinating between differences, differences that get experienced as serendipity.

My understanding of how urban planning has evolved is that there’s now a significant appreciation for “mixed-use developments” – recognizing that multiple purposes embedded in a given space allow life to flourish. People will adapt and exapt creative uses out of any given space.

From mom-and-pop stores to busking performers, it is precisely where we don’t define how a space should be used that life emerges.3

The dinner table is for more than the consumption of sustenance. The town square for more than just pigeons. The bedroom for more than sleeping. Et cetera.

All these examples can be summarized in frames found in the study of Ecology. An ecosystem is more resilient and adaptive when it is more interconnected. When we build our living environments with interconnectivity in mind, we create more suitable living environments.

If we were to imagine the social fabric somewhat literally, one might imagine a homogenous social environment as a flimsy, homogenous sheet of fabric; undifferentiated and easy to tear:

As the social environment starts to gain character, perhaps the local hospital is known for its compassion and community programs, the fabric gains details. It starts to accrue some interesting designs and the needlework becomes more refined. Parts of it would have more stitching, creating regions of strength.

Eventually, as the social environment deepens in complexity, perhaps the hospital partners closely with a university, developing its artistic production, while the laboratory nearby produces innovative technology, the fabric gains heft and depth. It forms an intricate, beautiful piece of lasting art.

The more purposes or meaning we embed into a “space”, the more it is potentiated for life. Conveniently, humans (and life) are naturally drawn to adding purpose to a space that permits it. However, it is also humans that define and through it often confine a space to specific activities. The school is for classes, the hospital for doctors and patients, the factory for production, etc. Through the act of defining the singular purpose of a given space, our imagination is subtly, yet forcefully, invited to cease: “This is the classroom, it is for learning. If you want to play, do it outside!” Scarier still, when we are trained under this mode of categorization, whole humans increasingly get categorized too: Mr. Bell is a teacher who teaches math at school – to find out that Mr. Bell is a neighbor would be mighty strange.

We can not do without the act of categorizing. It helps us organize. Yet, to categorize, or to differentiate, does not require the separation of the categorized object’s other qualities. The sports arena may be converted to a basketball court one night, a concert hall, another. Its multi-purpose nature is what gives it its tallness. The concertgoer and the sports fan can both ascribe their different relationships to the arena, contributing to its tallness. In that tallness, that concertgoer and the sports fan may end up crossing paths, forming new relationships only possible through the interconnectivity inherent in “Tallness”.

A sense of place is built up, in the end, from many little things too, some so small people take them for granted, and yet the lack of them takes the flavor out of the city … The remarkable intricacy and liveliness of downtown can never be created by the abstract logic of a few men. Downtown has had the capability of providing something for everybody only because it has been created by everybody. — Jane Jacobs, Downtown Is For People, 1958

In addition to the “everybody”, referring to citizens who build up a city, another class of actors is left out of the picture – institutions. A significant influence that rivals the people themselves, institutions are also an inevitable feature of spaces with tallness. I will go into this in the next part.

Meanwhile, as part of the “everyone”, each mark we leave on our environment is an act of building it. From our private rooms to our public spaces, we create the tall city by etching our life into its spaces.

To be “tall” is to be imbued with complexity, with life. Tallness isn’t only density, but rather a density of differences, a density of plurality, a plurality that endures.

Much of this post is a re-presentation of the work of Christopher Alexander, which I highly recommend. While subsequent posts diverge from the kind of illustration Alexander does, many of his ideas around Life and Wholeness undergird the notion of “Tallness” as I illustrate in these posts.

I really like walking through cities. I could do days of just walking, especially in the case of Tokyo lol. Instead of going to each of the known tourist spots, I like to take a relatively random path and instead walk by whichever direction seems most interesting (or most tall I suppose). I find I am able to feel the city much deeper in this way. In cases like these parks, I tend to hit them accidentally, which made the experience even more striking and delightful. Tokyo, as a physical city (less so in other dimensions), is such an epitome of this quality of tallness that it’s honestly staggering.

This is why in city building simulators, the game can at most “simulate” life through the variety of buildings or the simulacrum of people programmed to interact with each other, but there’s a hard limit to how much life we can program in via management. In an important sense, these city simulators are management simulators not a life simulators.

Really enjoyed this piece! Especially coming out of a recent city council meeting that deferred approval of removing zoning restrictions that prevent small businesses from opening within neighbourhoods in Toronto. A policy proposal with a 95% public approval rating, yet hindered by one woman's campaign against it.

I have been thinking about the ways in which constraints and freedoms interplay to allow for emergent complexity with the kinds of aliveness and vitality that you describe here. The juxtaposed images convey how this quality is something beyond single factors like density or difference. What does allow a 'tall' quality to develop?

Love that description of what a "rich" social fabric can actually mean. The analogy to brain surface area feels resonant